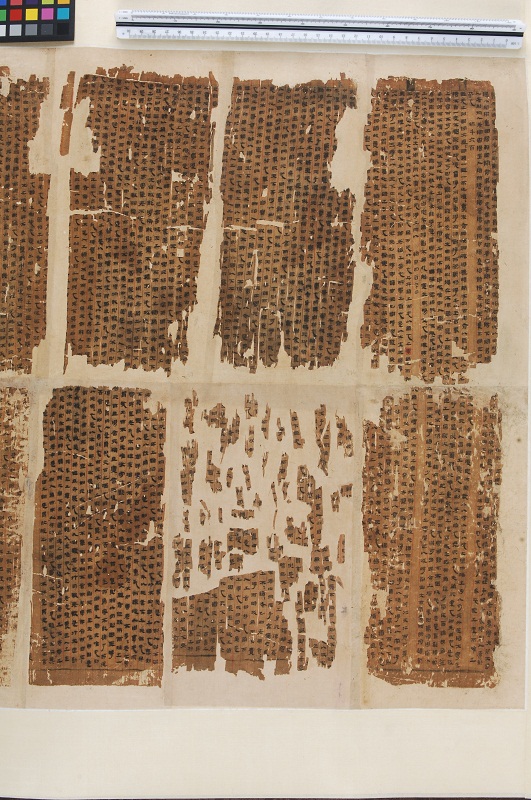

Silk Book of Laozi (Version B)

Western Han Dynasty (206BC—25AD)

Length: 79.5 cm; Width: 55 cm

Excavated from Tomb No.3 at Mamangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, in 1973

Silk Book of Laozi (Version B) was found from the lower layer of an oblong lacquer cosmetic box found in the eastern case of the Tomb 3. It was copied onto a breadth of wide silk together with four ancient canons. As it was folded up, the book broke into 32 pieces when discovered.

The book was copied in very neat early official script, making it a precious material for studying the change of the Chinese character and the art of calligraphy.

As this version avoid the taboo of mentioning the name of Liu Bang but does not avoid mentioning the name of Liu Hui, Emperor Huidi, the time of its being copied should be during the reign of Emperor Huidi or Empress Lu. This version has The Book of De preceding The Book of Dao.

Laozi is the most important document of China’s Daoism. The discovery of this 2000-year-old Version B of Laozi is of great value to the collation of the chapter sequence of existing versions of Laozi. It has also provided new resources for studying the ideology of Daoism and the spread of Daoism in the Han Dynasty. This version has no division of chapters and the sequence of chapters is exactly the same as Version A, with only some minor differences. Compared with traditional versions of Laozi, this silk version shows clearer ideas and richer contents.

深入探索

About Laozi

Confucianism, Daoism (Taoism), and Buddhism are commonly regarded as the three main pillars of traditional Chinese thought. Among which, philosophical Daoism traces its origins to Laozi, who flourished during the sixth century B.C.

The name “Laozi” is best taken to mean “Old (lao) Master (zi),” and Laozi the ancient philosopher is said to have written a short book, which has come to be called simply the Laozi. When the Laozi was recognized as a “classic”(jing) — that is, accorded “canonical” status, so to speak, on account of its profound insight and significance — it acquired a more exalted and hermeneutically instructive title, Daodejing, commonly translated as the “Classic of the Way and Virtue.” It is concerned with the Dao or “Way” and how it finds expression in “virtue” (de), especially through what the text calls “naturalness” (ziran) and “nonaction” (wuwei).

Its influence on Chinese culture is pervasive, and it reaches beyond China. Next to the Bible, the Daodejing is the most translated work in world literature. These concepts, however, are open to interpretation. While some see them as proof that the Laozi is a deeply “mystical” work, others emphasize their contribution to ethics and/or political philosophy. Interpreting the Laozi demands careful hermeneutic reconstruction, which requires both analytic rigor and an informed historical imagination.

Silk Book of Laozi (Version A) (206—195 BC)

Excavated from Tomb No.3 at Mamangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, in 1973

From the collection of Hunan Provincial Museum

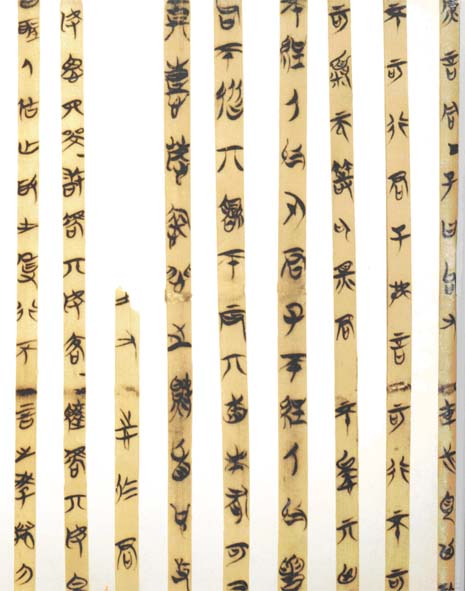

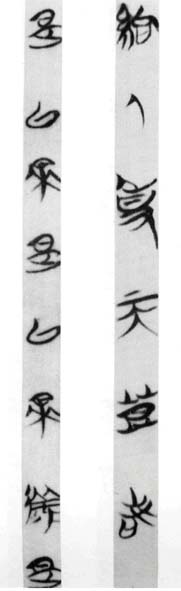

Inscribed Bamboo Slips of Laozi (Version A)

Excavated from Chu Tomb No.1, Guodian, Jingmen, Hubei Province

One of the earliest copied books of Laozi ever found by far

Inscribed Bamboo Slips of Laozi (Version B)

Excavated from Chu Tomb No.1, Guodian, Jingmen, Hubei Province

One of the earliest copied books of Laozi ever found by far

Inscribed Bamboo Slips of Laozi (Version C)

Excavated from Chu Tomb No.1, Guodian, Jingmen, Hubei Province

One of the earliest copied books of Laozi ever found by far